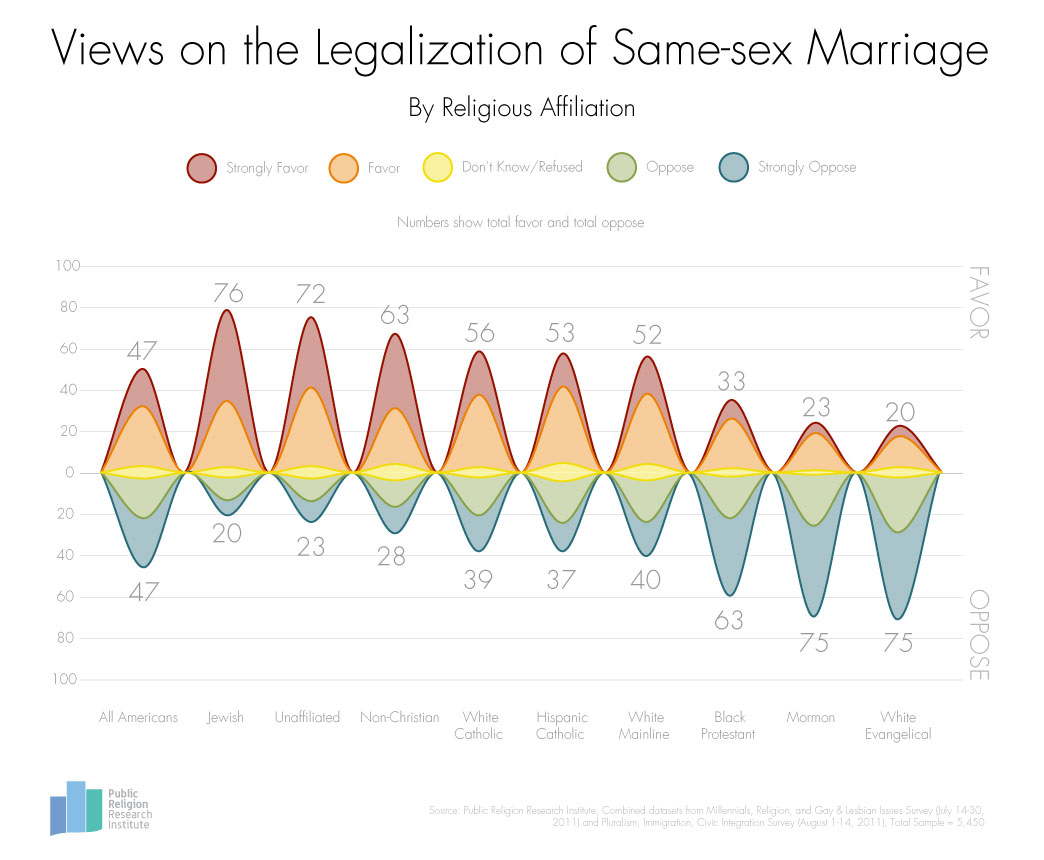

The source data (via PRRI) are almost three years old now, no doubt in the intervening years things have shifted up towards the pro-equality side of the ledger. Mormons and White Evangelicals remain the reigning champions of anti-LGBT sentiment, however, and they are demographically concentrated in areas with low religious diversity, including the American South and Oklahoma, where lawmakers are nearly always bound to reflect the biases and beliefs of the religious majority.

We secularists need to develop an argument which will allow us to win the affiliations on the far right over on this particular issue, that is, one which allows them to separate their sacred idea of marriage from our broadly shared secular concept of marriage which applies to people of all faiths and none. Parties to the latter have rights and duties under civil law, whereas parties to the former are accountable to whichever god or gods they profess, whether via conscience or clergy. Once evangelicals can come to accept that they are held to a different (in their minds, higher) standard respecting marriage than society at large, they should be able to separate the rules of holy writ from those of civil law. Oddly enough, just such an argument was put forward long ago by that lion of evangelical Christianity, C.S. Lewis, writing on a somewhat different question about whether the Christian conception of marriage should be the legal standard for all citizens:

The Christian conception of marriage is one: the other is quite the different question—how far Christians, if they are voters or Members of Parliament, ought to try to force their views of marriage on the rest of the community by embodying them in the divorce laws. A great many people seem to think that if you are a Christian yourself you should try to make divorce difficult for every one. I do not think that. At least I know I should be very angry if the Mohammedans tried to prevent the rest of us from drinking wine. My own view is that the Churches should frankly recognize that the majority of the British people are not Christian and, therefore, cannot be expected to live Christian lives. There ought to be two distinct kinds of marriage: one governed by the State with rules enforced on all citizens, the other governed by the church with rules enforced by her on her own members. The distinction ought to be quite sharp, so that a man knows which couples are married in a Christian sense and which are not.

Such a simple and elegant solution! All sects may continue to preach to their own parishioners about exactly how marriage should be, and the churches may strive to change the cultural face of marriage using moral suasion and rhetoric rather than force of law, just as Jesus did.