Last night, President Obama got huge applause for calling out the aggregate gender pay gap in the U.S. “Today, women make up about half our workforce,” he said. “But they still make 77 cents for every dollar a man earns. That is wrong, and in 2014, it’s an embarrassment. A woman deserves equal pay for equal work.”

Everyone who values fairness should agree that people deserve to be paid the same for performing the same work, but it is misleading to imply that women and men are generally doing the same work. While there are several professions where the gender ratio is nearly fifty-fifty, there are also quite a few fields in which it is heavily skewed one way or another, and the choice of profession is driving a huge portion of the statistical disparity overall, as noted by Blau and Kahn in their widely-cited 2007 paper on the gender wage gap:

[G]ender differences in occupation and industry are substantial and help to explain a considerable portion of the gender wage gap. Men are more likely to be in blue-collar jobs and to work in mining, construction, or durable manufacturing; they are also more likely to be in unionized employment. Women are more likely to be in clerical or professional jobs and to work in the service industry. Taken together, these variables explain 53% of the gender wage gap–27% for occupation, 22% for industry, and an additional 4% for union status.

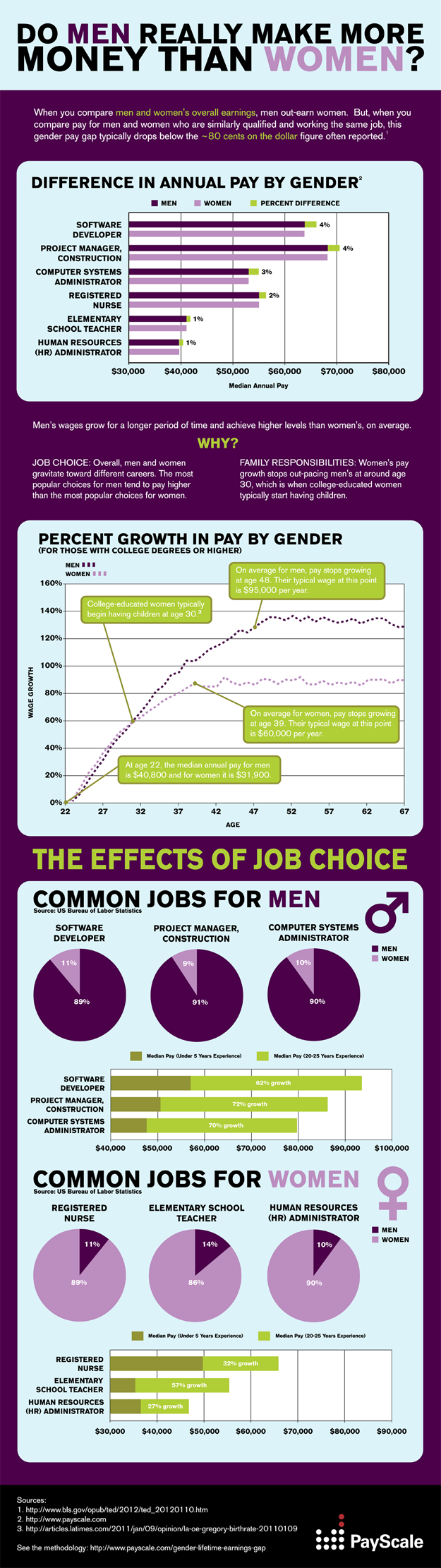

I was planning on making a chart to illustrate some of this, but then happened to came across this study at PayScale.com which included this handy infographic:

It is possible, of course, that the pay disparity between careers favored heavily by women and those mostly manned by men is (at least partly) the result of latent sexism on the part of those making hiring, budgeting and staffing decisions. Naturally, this would be a far more subtle and insidious problem than the sort of straightforward gender discrimination we would be facing if employers actually chose to pay women 77 cents on the dollar relative to men for doing the same job.

We cannot hope to effectively work towards equality if we are not willing to face up to the full complexity of the problem. In this case, that means we must address the disparate distribution of career choices, variation in work experience, and the spectre of the motherhood penalty. To simplify the pay gap down to a single statistic is wrong, and in 2014, it’s an embarrassment.