Last night, my wife was telling me about how she had to fix some of the answers on an upcoming clinical medicine examination because exciting new research had made one of the previously “incorrect” answers correct, it turns out that a certain drug does indeed have a certain (heretofore unproven) effect. I bring this up to point out that one of the cardinal skeptical virtues has become fairly ingrained among those who practice and teach science-based medicine, that is, the constant reevaluation and revision of the received body of knowledge.

In the field of history it is somewhat more difficult to practice this skeptical virtue, because the narratives are so firmly ingrained and striking new evidence only rarely overturns previously held beliefs. That being the case, it is nonetheless essential to skeptically examine the historical narratives which have been handed down, not least because such narratives often serve political purposes. Today, I’d like us to skeptically reconsider whether the United States was indeed “born on the 4th of July,” as they say.

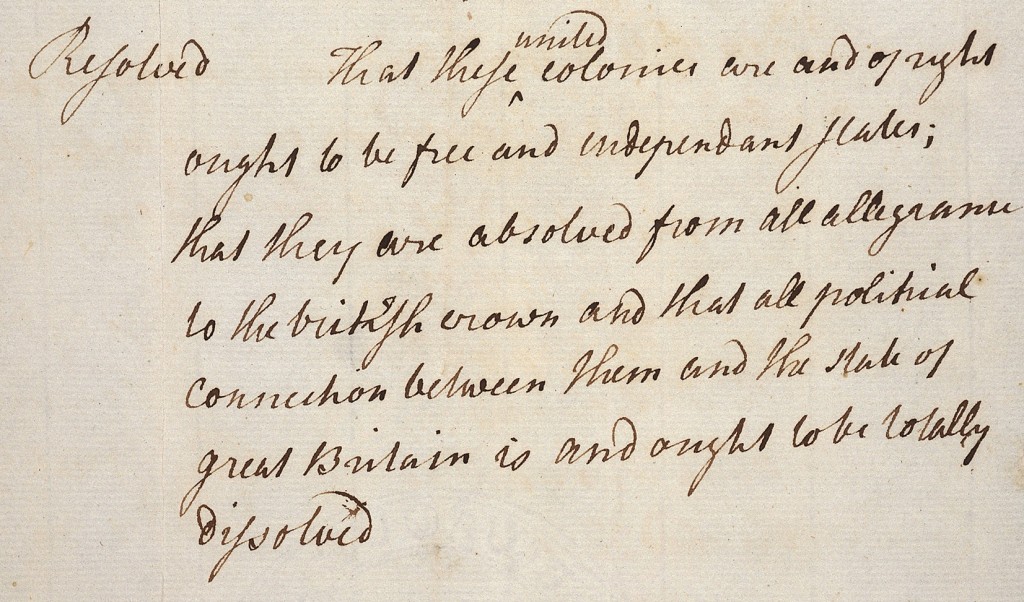

There is no new evidence to be had here, it has long been known that the Second Continental Congress approved the first clause of the Lee Resolution on July 2, 1776, reading as follows:

Resolved, That these United Colonies are, and of right ought to be, free and independent States, that they are absolved from all allegiance to the British Crown, and that all political connection between them and the State of Great Britain is, and ought to be, totally dissolved.

On the heels of this resolution, John Adams wrote to his wife of the celebrations that would follow:

The Second Day of July 1776, will be the most memorable Epocha, in the History of America.—I am apt to believe that it will be celebrated, by succeeding Generations, as the great anniversary Festival. It ought to be commemorated, as the Day of Deliverance by solemn Acts of Devotion to God Almighty. It ought to be solemnized with Pomp and Parade, with Shews, Games, Sports, Guns, Bells, Bonfires and Illuminations from one End of this Continent to the other from this Time forward forever more.

He was right about the celebrations, of course, but off just a bit on the date, because Americans came to celebrate not the Lee Resolution but rather the formal announcement thereof, that is, the Declaration of Independence, the text of which was adopted by the Second Continental Congress two days later. If July 2nd marked the legal birth of a new national entity, July 4th could be thought of as an elaborately worded birth announcement. It is perhaps telling that we chose as a nation to pay homage to the stylistic declaration rather than the substantive resolution, but I hope not to read too much into that at this late date.

There are several other dates we could have chosen from to mark the beginning of the United States as a nation. One could go all the way back to April 19, 1775 and the opening of military hostilities between British regulars and American minutemen, hostilities which would eventually make independence a foregone conclusion. One could go all the way forward to March 4, 1789 when the current Constitution first took effect, thus marking the beginning of the United States government as we know it. The general skeptical lesson here may be that whenever we mark a particular fixed date as the beginning of some grand venture, we run the risk of vastly oversimplifying the complex process of interlocking economic, demographic, cultural and intellectual forces that lead up to that date and beyond it.