Some weeks ago, I presented several translations of the Book of Daniel, chapter 9, verses 20-27. I showed how the Jewish and Christian versions–that is, the very texts provided for reading–indicated radically different approaches. We saw that in specific words, phrases, capitalization and punctuation, the translations encourage the very understanding a translator/editor wants the reader to get.

For example, it is much easier to read Jesus into this text–

20. While I was speaking and praying, confessing my sin and the sin of my people Israel and making my request to the Lord my God for his holy hill—

21. while I was still in prayer, Gabriel, the man I had seen in the earlier vision, came to me in swift flight about the time of the evening sacrifice.

22. He instructed me and said to me, “Daniel, I have now come to give you insight and understanding.

23. As soon as you began to pray, a word went out, which I have come to tell you, for you are highly esteemed. Therefore, consider the word and understand the vision:

24. “Seventy ‘sevens’ are decreed for your people and your holy city to finish transgression, to put an end to sin, to atone for wickedness, to bring in everlasting righteousness, to seal up vision and prophecy and to anoint the Most Holy Place.

25. “Know and understand this: From the time the word goes out to restore and rebuild Jerusalem until the Anointed One, the ruler, comes, there will be seven ‘sevens,’ and sixty-two ‘sevens.’ It will be rebuilt with streets and a trench, but in times of trouble.

26. After the sixty-two ‘sevens,’ the Anointed One will be put to death and will have nothing. The people of the ruler who will come will destroy the city and the sanctuary. The end will come like a flood: War will continue until the end, and desolations have been decreed.

27. He will confirm a covenant with many for one ‘seven.’ In the middle of the ‘seven’ he will put an end to sacrifice and offering. And at the temple he will set up an abomination that causes desolation, until the end that is decreed is poured out on him.”

than it is to read him into this one–

20. And whilst I was speaking, and praying, and confessing my sin and the sin of my people Yisra’el, and presenting my supplication before the Lord my God for the holy mountain of my God;

21. whilst I was still speaking in prayer, the man Gavri’el, whom I had seen in the vision at the beginning, approached close to me in swift flight about the time of the evening sacrifice.

22. And he made me understand, and talked with me, and said, O Daniyyel, I am now come forth to give the skill and understanding.

23. At the beginning of thy supplications the commandment went out, and I am come to declare it; for thou art greatly beloved: therefore look into the word, and consider the vision.

24. Seventy weeks are decreed concerning thy people and concerning thy holy city, to finish the transgression, and to make an end to sins, and to atone for iniquity, and to bring in everlasting righteousness, and to seal up vision and prophet, and to anoint the most holy place.

25. Know therefore and understand, that from the going forth of the commandment to restore and to build Yerushalayim until an anointed prince, shall be seven weeks: then for sixty two weeks it shall be built again, with squares and moat, but in a troubled time.

26. And after sixty two weeks shall an anointed one be cut off, and none will be left to him: and the people of a prince that shall come shall destroy the city and the sanctuary; and his end shall be with a flood, and to the end of the war desolations are decreed.

27. And he shall make a strong covenant with many for one week: and during half of the week he shall cause the sacrifice and the offering to cease; and upon the wing of abominations shall come one who makes desolate, until the decreed destruction is poured out on the desolator.

Clearly, the first one is a Christian text and the second is a Jewish text, and the differences are striking. To take but one example, in the Jewish text, the “prince that shall come” is prophesied to die by flood, but in the Christian text it is the destruction of Jerusalem that will come like a flood.

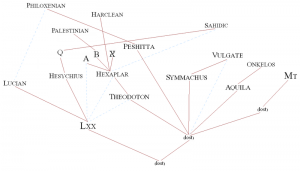

Is one approach or version to be preferred over another? Perhaps, but consider that the translations are themselves based on texts that redact even earlier versions. What is considered the authoritative text of the Hebrew Bible is called the Masoretic Text (MT). Helpfully, the MT includes vowels and vocalizations, which were not provided in earlier versions. Indeed, the mark of literate skill was being able to read the text properly without many of the visual cues we take for granted in modern textual practice.

The MT, in other words, crystallizes an orthodox reading of texts that were presented and perhaps read differently–maybe much differently before. In fact, one of my favorite books, How to Read the Bible by James Kugel, makes this very point. It was a certain way of approaching ancient Israel’s library that in the three centuries before the common era transformed an assembled collection of books into “The Bible,” a holy work and central moral authority.

I do not want to belabor the point, but when we look at biblical verses, their book histories, and their interpretations, what we always see is a chain of evolving views and convergent orthodoxies. Whenever I get into subjects like this I wonder what would have happened if one scholar prevailed over another, or if a different text had been interpolated, or if the timing and provenance had been changed ever so slightly. I believe that were the tape of history to be re-wound and started again, the resulting holy books and religious events would be very different from the history we know.

So, the Christian and Jewish approaches are what they are. When it comes to the Book of Daniel, one may find a certain approach more satisfying than another, but the truth of the interpretations is never actually on the table. Neither approach is able to produce fact-based truth because the texts we have preclude it. The fact is that the text does not name or explicitly refer to the anointed prince by name. To name that prince Cyrus or Nehemiah or Jesus or Uncle Lou is to read into the text. I dare say that reading in is precisely what we are supposed to do; it’s the reading in, not the truth, that’s in play.

Besides the deliberately cryptic nature of the text, Daniel’s language is a key piece of evidence suggesting that the book is not one of truth but of interpretation. Analysis of Daniel from the perspective of historical linguistics yields four different apocalyptic authors and content/language that puts the book still being written into the second century BCE. Daniel himself would have been a sixth-century BCE person. This means that many of the prophecies in Daniel’s mouth are history from the point of view of the book’s authors and/or compilers.

William Shakespeare was particularly adept at making men into prophets. Over 100 years after the violence and political instability of the Wars of the Roses, Shakespeare’s Richard II views the deposing of Richard as the fatal act that would bring calamity to the isle. Carlisle, appropriately enough a Bishop, issues the prophecy in Act IV, scene i:

Worst in this royal presence may I speak,

Yet best beseeming me to speak the truth.

Would God that any in this noble presence

Were enough noble to be upright judge

Of noble Richard! then true noblesse would

Learn him forbearance from so foul a wrong.

What subject can give sentence on his king?

And who sits here that is not Richard’s subject?

Thieves are not judged but they are by to hear,

Although apparent guilt be seen in them;

And shall the figure of God’s majesty,

His captain, steward, deputy-elect,

Anointed, crowned, planted many years,

Be judged by subject and inferior breath,

And he himself not present? O, forfend it, God,

That in a Christian climate souls refined

Should show so heinous, black, obscene a deed!

I speak to subjects, and a subject speaks,

Stirr’d up by God, thus boldly for his king:

My Lord of Hereford here, whom you call king,

Is a foul traitor to proud Hereford’s king:

And if you crown him, let me prophesy:

The blood of English shall manure the ground,

And future ages groan for this foul act;

Peace shall go sleep with Turks and infidels,

And in this seat of peace tumultuous wars

Shall kin with kin and kind with kind confound;

Disorder, horror, fear and mutiny

Shall here inhabit, and this land be call’d

The field of Golgotha and dead men’s skulls.

O, if you raise this house against this house,

It will the woefullest division prove

That ever fell upon this cursed earth.

Prevent it, resist it, let it not be so,

Lest child, child’s children, cry against you woe!

Hallelujah! As we see, prophecy is a great way of communicating a moral view of certain original events. Prophecies connect the past with the present, and warn people today not to make the same mistakes their ancestors did.

Nevertheless, my point is that every attempt to fit Jesus or some other messiah into the paradigm of Daniel ultimately amounts to coding. By coding, later events become the “true” references of a text made cryptic. The text now means something else, something more than what it says on the surface. And who holds the key to unlock these secret meanings? The priests.

I don’t mean to sound entirely cynical because most every profession I know is a kind of priestly caste with respect to its area of expertise. A doctor knows the secrets of the human body and of medicines. An economist reads financial signs to predict market developments.

But I have little regard for any priesthood because they do not offer knowledge. They offer teaching, which is certainly valuable but improves us more when coupled with truth, or even provisional truth. And so my opinion of the Christian and Jewish interpretations of Daniel is the same, which is to say not particularly high. In Kugel’s book, mentioned earlier, the suggestion is that modern biblical scholarship offers only what amounts to a different interpretation, something at the same level as the Christian or Jewish ones, although Kugel favors the ancient and orthodox Jewish view.

I disagree, of course. The ultimate context of the better interpretation has to converge upon our best knowledge of history and reality. The view that Daniel’s apocalyptic messages are, finally, literature alone is the view most consonant with reality, and so I stand to that side.