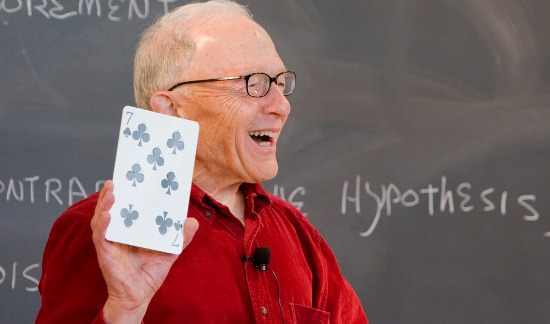

Ray Hyman’s accomplishments on behalf of science, science advocacy, and skepticism are legion- enough to fill many pages. I will forego a list up front, partly because the interview proper discusses them and partly because the external links at the end do a far better job than I could. What really impresses me about Mr. Hyman is, in a word, class. He has a reputation for being respected and even liked by his academic and skeptical cohorts, but also by the parapsychology claimants he has so often criticized. He has, to an astonishing degree, internalized and behaved according to the scientific precepts of objective consideration and the detangling of ego and truth. In his written works and public appearances, he is consistently far more concerned with fomenting reason than agreement; he cultivates understanding while most of us chase mindshare. If James Randi is skepticism’s much-needed sentinel-sheriff, Ray Hyman is an impartial judge & jury, injecting some honesty and fairness in a factious land.

Skeptic Ink: You are one of the prominent figures in the history of contemporary skepticism, along with James Randi and Martin Gardner and others. First off, please briefly explain how you got involved, given your background as a mentalist and magician, and your long academic career as a psychologist.

Ray Hyman: I did my first magic show for money at age 7. A few years later I read a biography about Houdini. In addition to his feats as an escape artist and his career as a magician, the biography highlighted his efforts at debunking spirit mediums and phony psychics. From reading this book, I assumed that being a magician entailed investigating and debunking psychic claims. So, as far back as I can remember, I always believed that I should investigate, understand, and challenge paranormal claims. Beginning in the 1950s, I began writing for both lay and professional audiences on paranormal claims. Since that time, I have served on government and professional committees investigating paranormal and controversial claims.

In December, 1972, I was sent by the Advanced Research Projects Agency of the Defense Department to look at the experiments that two physicists at the Stanford Research Institute were conducting with Uri Geller. Soon after that Randi, acting as one of the reporters from Time Magazine, saw Geller perform his stunts. These encounters with Geller prompted Randi to meet with me in 1973 to discuss the possibility of forming an organization to help protect both scientists and the public from such scams.

Martin Gardner, Randi and I formed an organization we called SIR (an acronym that stood for “Sanity in Research.” SIR was an anagram of SRI (Stanford Research Institute). In 1976, SIR joined forces with Paul Kurtz and a few others to create CSICOP (The Committee for the Scientific Investigation of Claims of the Paranormal). And the rest is history.

SI You have a reputation for being one of the “fair-minded skeptics.” Do you think the skeptics movement is sometimes too closed-minded about paranormal or fringe-science claims?

RH Most people who call themselves “skeptics”(as well as believers) are closed-minded, dogmatic, and militant in their beliefs. The word “skeptic” has a variety of meanings. Historically and philosophically, it refers to a person who withholds judgment about a claim until a preponderance of evidence accumulates either for or against it. Once the person takes a position about a claim, he/she is no longer skeptical with respect to the claim, but is dogmatic (not necessarily in a pejorative sense). The public and our critics equate skepticism with denialism and negativism. The media thrive on controversy and sharp distinctions between believers and “skeptics.” They find the reasoned, and non-dogmatic, arguments of true skeptics too subtle for their tastes.

RH Most people who call themselves “skeptics”(as well as believers) are closed-minded, dogmatic, and militant in their beliefs. The word “skeptic” has a variety of meanings. Historically and philosophically, it refers to a person who withholds judgment about a claim until a preponderance of evidence accumulates either for or against it. Once the person takes a position about a claim, he/she is no longer skeptical with respect to the claim, but is dogmatic (not necessarily in a pejorative sense). The public and our critics equate skepticism with denialism and negativism. The media thrive on controversy and sharp distinctions between believers and “skeptics.” They find the reasoned, and non-dogmatic, arguments of true skeptics too subtle for their tastes.

SI Your influential essay “Proper Criticism” lists eight points of advice (see aside below) for fairly engaging believers. Do you think the message is as relevant to the skeptics movement today as it was when you first published it in your book The Elusive Quarry and in the pages of Skeptical Inquirer magazine?

RH Yes.

SI Are there any aspects of pseudoscience or the paranormal that you feel the scientific community has conclusively resolved and that therefore merit no further critical attention?

RH I am not sure I understand this question. I think a more meaningful question would be: “Are there any aspects of pseudoscience or the paranormal that you feel the scientific community should consider for scientific investigation?” My answer would be, “No.” The program for parapsychology is incoherent.

Psychical research, which is the original name for what is now called parapsychology, was initiated with the specific goal to scientifically demonstrate that there are phenomena that cannot be captured by science. As such, the program has been incoherent from the start. Parapsychologists have no positive theory or model of the phenomena they claim to be studying. What they call “psi” is defined and identified negatively. They claim having demonstrated the existence of “psi” whenever they obtain a statistically significant result which cannot be readily explained by mundane causes. This strategy has many undesirable problems from a scientific perspective. For one thing, it is impossible to discover every possible normal cause in a particular experiment. For another, this allows them to claim any departure from chance as evidence for psi.

SI In your interview (below) a couple years ago with D.J. Grothe, when National Capital Area Skeptics presented you with the Phillip J Klass Award for your outstanding contributions in promoting critical thinking and scientific understanding, you seemed to suggest that if Randi and you have had different approaches in dealing with paranormalists, you now believe his approach is better for public education (his approach being more directly confrontational as opposed to the more tentative, academic approach you have taken). Do you still hold this view?

RH I am an academic. My typical audience consists of academics and scholars who often are suspicious of what they see as Randi’s theatrics and negativism. Although some of my academic friends are great fans of Randi, most find his approach off-putting. I have found that for most of my audiences, a less confrontational and rational approach is more successful. For the general public, however, I have no doubts that Randi’s approach succeeds very well.

RH I am an academic. My typical audience consists of academics and scholars who often are suspicious of what they see as Randi’s theatrics and negativism. Although some of my academic friends are great fans of Randi, most find his approach off-putting. I have found that for most of my audiences, a less confrontational and rational approach is more successful. For the general public, however, I have no doubts that Randi’s approach succeeds very well.

SI There have been many controversies over the years of organized skepticism, including disagreements about the proper scope of skepticism, and the role of atheism, social justice movements, and politics within the skeptics movement. Do you think that the scientific skepticism has something relevant to say to the world of politics, religion and social justice movements?

RH I am a strong believer that the scientific method is the only reliable and trustworthy method for achieving knowledge. Many questions and issues that occupy politics, religion, social justice and related movements cannot be answered by scientific investigation. Some obviously can. Still others, which previously were thought to be outside the purview of science, later become tractable. What disturbs me is how often these disciplines make claims that can and should be settled by empirical scientific investigations. For example, many Republicans have campaigned on platforms that claim that climate change is an issue that can be settled by political fiat. Religion often attempts to overrule scientific evidence on issues such as creation, birth, abortion, etc. I have been quite dismayed at how many religious, social science and other individuals have been demonizing science and declaring that scientific knowledge is merely a matter of social and political consensus.

RH I am a strong believer that the scientific method is the only reliable and trustworthy method for achieving knowledge. Many questions and issues that occupy politics, religion, social justice and related movements cannot be answered by scientific investigation. Some obviously can. Still others, which previously were thought to be outside the purview of science, later become tractable. What disturbs me is how often these disciplines make claims that can and should be settled by empirical scientific investigations. For example, many Republicans have campaigned on platforms that claim that climate change is an issue that can be settled by political fiat. Religion often attempts to overrule scientific evidence on issues such as creation, birth, abortion, etc. I have been quite dismayed at how many religious, social science and other individuals have been demonizing science and declaring that scientific knowledge is merely a matter of social and political consensus.

Skeptic Ink thanks Mr. Hyman for the interview.

Read more about Ray Hyman

Wikipedia

CSICOP Articles

University of Oregon Professor Emeritus

Ray Hyman’s 8 suggestions for fairly engaging believers. Full essay here.

Be prepared.

Good criticism is a skill that requires practice, work, and level-headedness. Your response to a sudden challenge is much more likely to be appropriate if you have already anticipated similar challenges. Try to prepare in advance effective and short answers to those questions you are most likely to be asked. Be ready to answer why skeptical activity is important, why people should listen to your views, why false beliefs can be harmful, and the many similar questions that invariably are raised. A useful project would be to compile a list of the most frequently occurring questions along with possible answers.

Whenever possible try your ideas out on friends and “enemies” before offering them in the public arena. An effective exercise is to rehearse your arguments with fellow skeptics. Some of you can take the role of the psychic claimants while others play the role of critics. And, for more general preparation, read books on critical thinking, effective writing, and argumentation.

Clarify your objectives.

Before you try to cope with a paranormal claim, ask yourself what you are trying to accomplish. Are you trying to release pent-up resentment? Are you trying to belittle your opponent? Are you trying to gain publicity for your viewpoint? Do you want to demonstrate that the claim lacks reasonable justification? Do you hope to educate the public about what constitutes adequate evidence? Often our objectives, upon examination, turn out to be mixed. And, especially when we act impulsively, some of our objectives conflict with one another.

The difference between short-term and long-term objectives can be especially important. Most skeptics, I believe, would agree that our long-term goal is to educate the public so that it can more effectively cope with various claims. Sometimes this long-range goal is sacrificed because of the desire to expose or debunk a current claim.

Part of clarifying our objectives is to decide who our audience is. Hard-nosed, strident attacks on paranormal claims rarely change opinions, but they do stroke the egos of those who are already skeptics. Arguments that may persuade the readers of the National Enquirer may offend academics and important opinion-makers.

Try to make it clear that you are attacking the claim and not the claimant. Avoid, at all costs, creating the impression that you are trying to interfere with someone’s civil liberties. Do not try to get someone fired from his or her job. Do not try to have courses dropped or otherwise be put in the position of advocating censorship. Being for rationality and reason should not force us into the position to seeming to be against academic freedom and civil liberties.

Do your homework.

Again, this goes hand in hand with the advice about being prepared. Whenever possible, you should not try to counter a specific paranormal claim without getting as many of the relevant facts as possible. Along the way, you should carefully document your sources. Do not depend upon a report in the media either for what is being claimed or for facts relevant to the claim. Try to get the specifics of the claim directly from the claimant.

Do not go beyond your level of competence.

No one, especially in our times, can credibly claim to be an expert on all subjects. Whenever possible, you should consult appropriate experts. We, understandably, are highly critical of paranormal claimants who make assertions that are obviously beyond their competence. We should be just as demanding on ourselves. A critic’s worst sin is to go beyond the facts and the available evidence.

In this regard, always ask yourself if you really have something to say. Sometimes it is better to remain silent than to jump into an argument that involves aspects that are beyond your present competence. When it is appropriate, do not be afraid to say, “I don’t know.”

Let the facts speak for themselves.

If you have done your homework and have collected an adequate supply of facts, the audience rarely will need your help in reaching an appropriate conclusion. Indeed, your case is made much stronger if the audience is allowed to draw its own conclusions from the facts. Say that Madame X claims to have psychically located Mrs. A’s missing daughter and you have obtained a statement from the police to the effect that her contributions did not help. Under these circumstances it can be counterproductive to assert that Madame X lied about her contribution or that her claim was “fraudulent.” For one thing, Madame X may sincerely, if mistakenly, believe that her contributions did in fact help. In addition, some listeners may be offended by the tone of the criticism and become sympathetic to Madame X. However, if you simply report what Madame X claimed along with the response of the police, you not only are sticking to the facts, but your listeners will more likely come the appropriate conclusion.

Be precise.

Good criticism requires precision and care in the use of language. Because, in challenging psychic claims, we are appealing to objectivity and fairness, we have a special obligation to be as honest and accurate in our own statements as possible. We should take special pains to avoid making assertions about paranormal claims that cannot be backed up with hard evidence. We should be especially careful in this regard when being interviewed by the media. Every effort should be made to ensure that the media understand precisely what we are and are not saying.

Use the principle of charity.

I know that many of my fellow critics will find this principle to be unpalatable. To some, the paranormalists are the “enemy,” and it seems inconsistent to lean over backward to give them the benefit of the doubt. But being charitable to paranormal claims is simply the other side of being honest and fair. The principle of charity implies that, whenever there is doubt or ambiguity about a paranormal claim, we should try to resolve the ambiguity in favor of the claimant until we acquire strong reasons for not doing so. In this respect, we should carefully distinguish between being wrong and being dishonest.

We often can challenge the accuracy or validity of a given paranormal claim. But rarely are we in a position to know if the claimant is deliberately lying or is self-deceived. Furthermore, we often have a choice in how to interpret or represent an opponent’s arguments. The principle tell us to convey the opponent’s position in a fair, objective, and non-emotional manner.

Avoid loaded words and sensationalism.

All these principles are interrelated. The ones previous stated imply that we should avoid using loaded and prejudicial words in our criticisms. If the proponents happen to resort to emotionally laden terms and sensationalism, we should avoid stooping to their level. We should not respond in kind.

This is not a matter of simply turning the other cheek. We want to gain credibility for our cause. In the short run, emotional charges and sensationalistic challenges might garner quickly publicity. But most of us see our mission as a long-run effort. We would like to persuade the media and the public that we have a serious and important message to get across. And we would like to earn their their trust as a credible and reliable source. Such a task requires always keeping in mind the scientific principles and standards of rationality and integrity that we would like to make universal.